Mud, Might, and Monarchy: The Architectural Legacy of Dahomey

The Artistic Grandeur and the Shadows of an Empire

Dahomey Royal Architecture: Power, Prestige, and the Shadows of an Empire

The Kingdom of Dahomey (c. 1600–1904), located in present-day Benin, was one of West Africa’s most formidable and artistically rich civilizations. Its royal architecture—centered around the palaces of Abomey—was a direct reflection of the kingdom’s military might, centralized monarchy, and cultural ingenuity. Constructed with locally sourced materials and adorned with striking bas-reliefs, Dahomey’s architectural legacy is both a testament to its grandeur and a reminder of the darker elements of its history, particularly its role in the transatlantic slave trade. Let’s step through the gates of history and explore the magnificence, function, and complexities of Dahomey royal architecture.

Origins and Architectural Significance

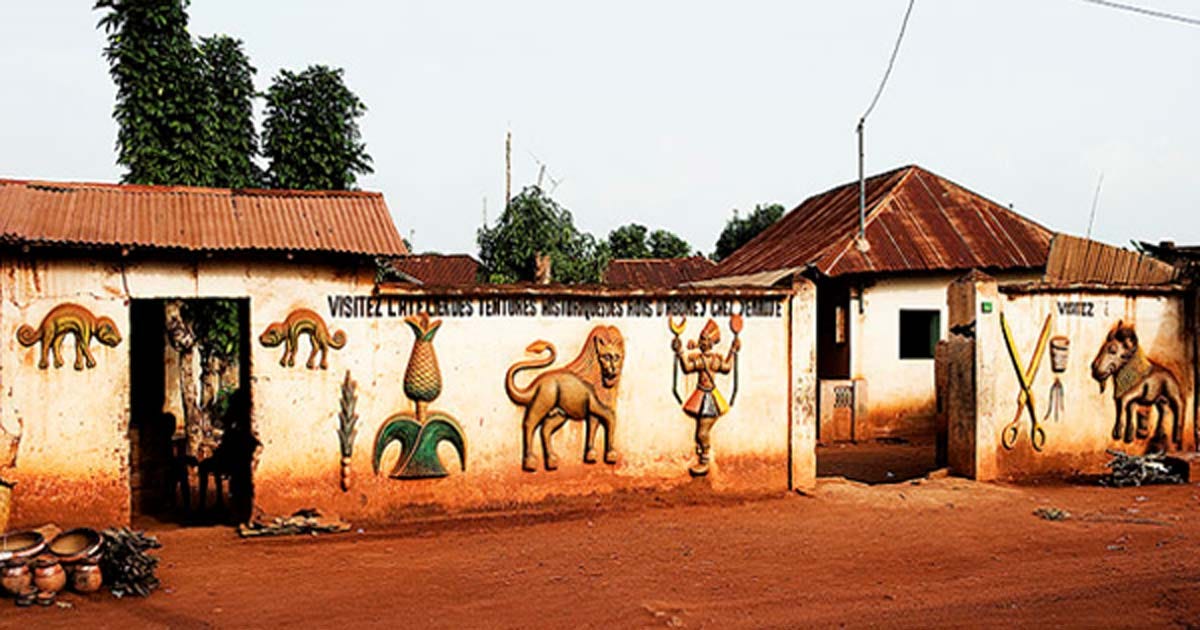

Dahomey’s royal architecture evolved alongside its expanding empire. The capital, Abomey, became the heart of its architectural development, featuring an elaborate palace complex that housed the ruling elite, military headquarters, and ceremonial spaces. The structures were designed to exude power, intimidate visitors, and reinforce the king’s divine authority. Unlike European-style castles or towering stone fortresses, Dahomey’s architecture relied on earthen materials and intricate artistry to showcase dominance.

Key Architectural Features

Adobe and Clay Walls – Thick walls made of sun-dried earth reinforced with organic materials, giving the structures longevity and insulation against the heat.

Striking Bas-Reliefs – Palaces were adorned with vivid, hand-carved bas-reliefs that depicted historical events, royal conquests, and symbols of authority.

Expansive Courtyards – Open spaces within the palace complex facilitated military parades, religious ceremonies, and court gatherings.

Layered Complexity – The palace structures were designed as a maze-like series of compounds, each serving a specific function for the king, his court, and his wives.

Sacred and Ritual Spaces – The architecture incorporated shrines to honor Vodun (Voodoo) deities, ancestors, and past monarchs.

Notable Dahomey Architectural Marvels

1. The Royal Palaces of Abomey

The most famous architectural legacy of Dahomey, these UNESCO-listed palaces served as the administrative and spiritual core of the kingdom. Built over multiple reigns, the complex housed:

The King’s Residence – Featuring richly decorated walls and a throne room with symbols of royal power.

The Hall of Skulls – A chilling chamber where the remains of defeated enemies were displayed as trophies of war.

The Female Warrior Barracks – Home to the elite all-female military corps, the Agodjie (known to Western audiences as the inspiration for the Dora Milaje in Black Panther).

The Dark Side of Dahomey’s Architectural Grandeur

While Dahomey’s architectural achievements were remarkable, they were deeply intertwined with the kingdom’s controversial role in the transatlantic slave trade.

Built on the Profits of Slavery – Many of Dahomey’s grand structures were financed through the sale of captives to European traders, leading to immense wealth for the ruling elite at the cost of human suffering.

Human Sacrifice Rituals – Some palace sites hosted ceremonies where prisoners of war were executed as offerings to Vodun deities, reinforcing the king’s spiritual and political legitimacy.

Political Oppression – The rigid hierarchical system ensured that commoners and conquered peoples had little access to the architectural grandeur reserved for the ruling class.

Resistance and Decline – By the 19th century, European powers, particularly the French, sought to dismantle Dahomey’s control over the slave trade. The kingdom’s resistance ultimately led to its downfall and the partial destruction of its palaces during French colonization.

Fun Facts About Dahomey Royal Architecture

Built to Last – Despite being constructed from earthen materials, parts of the Abomey palaces have stood for centuries, thanks to traditional construction techniques and periodic maintenance.

Royal Symbols in Reliefs – Each king had a unique emblem carved into palace walls, acting as both a signature and a historical record of their reign.

The Throne of Human Skulls – One Dahomey king was rumored to have used a throne made of enemy skulls to display his military dominance.

Women Warriors' Living Quarters – The Agodjie, one of the world’s most formidable all-female military units, had their own designated palace compound.

French Looting and Preservation – During the French conquest of Dahomey in the 1890s, many palace artifacts were taken to France, where they remain in museums today.

Legacy and Preservation

Despite Dahomey’s fall to colonial rule in 1894, its architectural legacy endures as a cultural and historical treasure.

UNESCO Recognition – The Royal Palaces of Abomey were designated a World Heritage Site in 1985, prompting efforts to preserve and restore their structures.

Modern Influence – Elements of Dahomey’s architectural style continue to influence contemporary Beninese architecture and artistic expression.

Cultural Reclamation – There has been growing advocacy for the return of Dahomey artifacts from Western museums, with some treasures recently repatriated to Benin.

Hollywood Influence – The kingdom’s history and its female warriors inspired the 2022 film The Woman King, bringing renewed global interest to its cultural and architectural heritage.

Mythology

Living Walls & Structural Ingenuity

Living Walls: Palace walls were built with terre crue (rammed earth) mixed with palm oil, creating a waterproof, termite-resistant material that hardened like concrete.

Blood Mortar: According to oral tradition, animal blood (and occasionally human blood from sacrifices) was mixed into mortar to spiritually fortify structures.

Thatch Mastery: Roofs were layered with intricately woven palm fronds, angled to funnel rainwater into hidden cisterns.

Beehive Engineering: Some storage rooms mimicked the natural cooling properties of beehives, staying 10°C cooler than the outside temperature.

Secret Passages & Defense Mechanisms

Secret Tunnels: The Abomey palaces had underground passages connecting royal chambers to armories and escape routes.

Spike Trenches: French invaders in 1892 noted trenches filled with poisoned spikes around Abomey, cleverly disguised under leaves.

Trapdoor Thrones: Kings could vanish via hidden floor panels during attacks, sliding into underground tunnels.

Fire Arrows: Palace rooftops held clay pots of flaming oil, ready to be lit and fired during sieges.

Design & Symbolism

Bas-Relief Chronicles: Palace walls featured polychrome clay bas-reliefs depicting battles, myths, and royal decrees—an ancient "comic book" of Dahomey history.

Skull Décor: Conquered enemies’ skulls were embedded into walls and throne platforms as symbols of power (later replaced with ceramic replicas).

Leopard Motifs: Leopard imagery adorned every palace, representing the king’s title: "The Leopard of the House."

Sacred Thresholds: Doorways were intentionally low, forcing visitors to bow when entering royal chambers.

Royal Color Code: Buildings were painted with natural pigments—red (power), white (purity), and indigo (spirituality).

Palace Complexes & Royal Innovations

12 Kings, 12 Palaces: Each of Dahomey’s 12 kings built a new palace within the Abomey complex, creating a sprawling "city within a city."

Warrior Walls: The 10 km-long Singboji wall surrounding Abomey was studded with spikes and guarded by hidden archer posts.

Amazon Quarters: The famed Mino (all-female warriors) had their own barracks within the palace, decorated with weapons and victory trophies.

Treasure Rooms: Palaces held akuebasi (royal vaults) filled with gold dust, Portuguese coins, and jewels from trans-Saharan trade.

Throne of Bones: King Ghezo’s throne (1818–1858) was mounted on the skulls of defeated enemies, including four European colonizers.

Cultural Fusion & Foreign Influences

Brazilian Influence: Enslaved Afro-Brazilian architects repatriated to Dahomey introduced arched doorways and stucco work in the 19th century.

Portuguese Tiles: Blue-and-white azulejo tiles from Portugal lined royal bathrooms, traded for palm oil and captives.

Yoruba Craftsmanship: Artisans from neighboring Yorubaland carved wooden pillars with Orisha (deity) motifs into Dahomey’s audience halls.

Islamic Geometry: Later palaces incorporated geometric patterns from North African traders, blending with traditional Dahomey symbols.

Innovations & Secrets

Fireproof Libraries: Royal archives were stored in clay-walled rooms with copper ventilation shafts to protect scrolls from humidity.

Acoustic Tricks: Whispering galleries in throne rooms allowed spies to eavesdrop on visitors.

Palm Wine Plumbing: Hollowed palm trunks channeled palm wine from fermentation rooms directly to royal feasting halls.

Night Illumination: Rooms were lit with oil lamps made from enslaved prisoners’ skulls (per French colonial accounts).

Quirky & Macabre Legends

Execution Decor: The Agbala (executioner’s courtyard) featured mosaics made from shattered enemy pottery and weapons.

Zombie Guards: Corpses of loyal soldiers were propped in niches to "stand watch" over treasure rooms (as reported by 19th-century explorers).

Royal Zoo: A palace annex housed exotic animals like hyenas and parrots, gifted by European traders.

Blood Moat: A trench filled with sacrificial blood and thorny plants surrounded the inner sanctum to repel evil spirits.

Ghost Towers: Empty watchtowers were left unfinished to confuse invaders, who assumed they were manned.

Legacy & Survival

UNESCO Scars: The Abomey palaces retain bullet holes from 1892 French attacks, preserved as part of their World Heritage status.

Stolen Thrones: France looted King Béhanzin’s throne in 1894; it’s now in Paris’ Musée du Quai Branly, despite repatriation demands.

Voodoo Syncretism: Today, palace courtyards host Vodun ceremonies where devotees commune with deified kings.

3D Revival: Archaeologists use photogrammetry to recreate destroyed sections of the palaces from 19th-century engravings.

Eco-Materials: Modern builders study Dahomey’s palm-oil mortar as a sustainable alternative to cement.

Myths & Mysteries

Cursed Bricks: Locals believe removing clay from the ruins brings misfortune—a myth that inadvertently protects the site.

Shape-Shifting Walls: Legends claim palace walls shifted layout at night to trap thieves.

Talking Drums: Hollow pillars in the throne room amplified drumbeats to mimic a "speaking palace" during rituals.

Immortal Masons: Oral histories say master builders were buried alive within walls to become eternal guardians.

Pop Culture & Modernity

Black Panther Vibes: The Abomey palaces inspired Wakanda’s throne room in Black Panther (2018).

Festival of Kings: Annual Zangbeto festivals feature masquerades where dancers emerge from palace ruins in costume.

NFT Art: Digital artists now animate Dahomey’s bas-reliefs as NFTs, reimagining battles in neon colors.

Wild Speculations

Hidden Gold: Rumors persist of undiscovered vaults beneath Abomey, possibly holding the lost treasures of King Glele.

Alien Theories: Fringe historians claim the precision of the earth walls implies "extraterrestrial guidance."

Time Capsules: Archaeologists found 19th-century gbo (Vodun charms) sealed in walls to protect future generations.

Musical Architecture: Certain walls hum in the wind, tuned to mimic traditional gongon drum rhythms.

Eternal Flame: A sacred fire in Guezo’s palace burned for 150 years, extinguished only by French troops in 1892.

Conclusion

Dahomey’s royal architecture is a striking blend of artistic ingenuity, political power, and historical complexity. From the imposing palaces of Abomey to the intricately carved reliefs narrating the kingdom’s conquests, these structures tell the story of a civilization that rose to prominence through military dominance and strategic governance. However, their grandeur is inseparable from the darker realities of the transatlantic slave trade and internal hierarchies. Today, efforts to preserve and interpret these sites help shed light on both the brilliance and the contradictions of one of West Africa’s most influential kingdoms.

So, as we explore the ruins of Abomey’s royal past, we are not just looking at the remnants of mud and clay—we are witnessing the echoes of an empire that left an indelible mark on African and world history.